by Felipe Nogueira

Dr. Brian

Hare is an associate professor in the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology

at Duke University and in the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience. Hare is a pioneer

and a key expert in the field of dog psychology. Together with Vanessa Woods,

Brian Hare has written about the revolution in the study of dog cognition in

the fascinating book The Genius of Dogs: How Dogs Are Smarter Than You Think.

The book, in their own words, is “about how cognitive science has come to

understand the genius of dogs through experimental games using nothing much

more high-tech than toys, cups, balls, and anything else lying around the

garage.”

Hare and other

researchers showed many times that dogs are good at understanding humans’

communicative intentions. With the help of a brilliant experiment with foxes begun

by Dmitri Belyaev in the 1950s and continuing to the present day, Hare’s

research uncovered what allowed dogs to develop this remarkable skill:

domestication After 45 generations, Belyaev’s foxes in the experimental group

had floppy ears, curled tails, and were much better reading human gestures than

the foxes in the control group. The key point is that Belyaev didn’t select for

foxes better at reading human gestures; instead he selected for foxes less

afraid and friendlier towards humans. As Hare and Woods note in their book: “Domestication,

selecting the friendliest foxes for breeding, had caused cognitive evolution.”

In order to

understand even more the limitations and flexibility of canine cognition, researchers

have created dedicated laboratories, such the Duke Canine Cognition Center,

created by Hare.

|

| Dr. Brian Hare |

Hare: If you’re

talking about high IQ, or who is going to be recruited to work for NASA, that

would make a very short book. In my opinion, the big discovery in the cognition

revolution is that cognition it’s not a unique dimensional trait. Actually, it’s

a whole set of skills that can vary independently and we don’t know how many

there are. For instance, one can be great at math, but a terrible communicator.

Regarding species, each one evolved to solve a set of problems that helped

them survive and reproduce in their particular environment; dogs are no

different. My book The Genius of Dogs

is all about trying to understand how a species that seems utterly unremarkable

can can be so successful. Dogs are successful from an evolutionary perspective

because, everywhere there are people, there are dogs. It’s the most successful

mammal—aside from humans and maybe cows. That’s what the book explores: do dogs have some

type of genius psychologically or cognitively? Yes, they show unusual degree of

sophistication and flexibility for solving problems.

Hare: Michael

Tomasello, a developmental psychologist and my research supervisor at the time,

was explaining to me how important gesture communication is in human

development. He thought it was not only crucial to human evolution but

something unique to humans. His theory was that kids developed the ability to

use human gestures and to understand communicative intention. Then I told him that

my dog could do the same thing. That’s when I learned what science is, because

even though it was an important idea for how humans evolved, Tomasello became

curious. He said to me: “I will help you to come up with a way to prove me

wrong.” That’s incredible! When he discovered that he was wrong about dogs, he

was excited, telling us to keep doing more experiments. People think science is

about people in lab coats coming up with genius ideas, but in reality it’s a

way to falsify ideas.

Nogueira: How was the first experiment

with dogs?

Hare: We use a

powerful, but very simple technique: we hide food in one of two containers.

Then we pointed to where we hide it, trying to help the dog search for it. Great-apes

are terrible at this task. They don’t show much cognitive flexibility, since they

have to learn the gesture. And every time you use a new gesture, they have to

learn again. In contrast, in kids around age 12 months, you can use gestures

they’ve never seen before, showing a degree of flexibility that it’s not seen

in great apes. With dogs we performed the same series of experiments that had been

done with apes and human children. The big surprise was that dogs are more like

children.

This was a controlled experiment: dogs were not using their noses nor reacting to motion. In science, there are two steps. First, you have to demonstrate a phenomenon. If it’s gravitational waves or dogs following gesture, you have to demonstrate the phenomenon. Then, you try to explain it. Often, people are so busy trying to explain something before they even demonstrate it exists. Once we demonstrated that dogs were following a pointing gesture, we wanted to know if they, for example, just smelled the hidden food. We found that wolves, dogs and foxes all preferred to use their eyes. When they can’t get the information they need from their eyes, then they use their nose. In these experiments, we found that dogs prioritize information from their eyes and memory over their nose.

Nogueira: One of the

fascinating experiments with dogs you mentioned in the book uses an opaque

barrier. Could you elaborate on it?

Hare: This is the

work of Juliane Kaminsky, Michael Tomasello, and Josep Call. They have placed a

ball behind two barriers, one opaque and one transparent. The dog can see both

balls. In the experimental condition, a human, on the opposite side of the

barriers, asks the dog to fetch the ball. The amazing thing is that dogs didn’t

take the ball from the opaque barrier, which the human can’t see through; they favored

the ball from the transparent barrier. In the control condition, where the

human and the dog are on the same side, seeing the same thing, the dog choose

the balls randomly. This experiment suggests that dogs know what humans can or

cannot see.

|

| Experiment conducted by Kaminski et al [2]. |

Hare: One level of explanation is that, since dogs have seen

these gestures several times, they slowly learned them. You can test this idea

by using a gesture they’ve never seen before, for instance, point with your

foot. You can also use a crazy gesture, like putting an object on top of the container

where the food is located. Human children and dogs follow those gestures, but

chimpanzees don’t. So, this hypothesis of slow learning was ruled out. But the

hard part is this: how do you know if dogs really have a sophisticated flexible

strategy, a theory of mind, which would mean that they’re thinking about the

thought of others individuals?. The best evidence about other animals that have

a theory of mind comes from great apes and maybe corvids. Regarding dogs, in fact,

we don’t have the smoking-gun experiment to rule out alternative explanations. Then,

we don’t have overwhelming evidence that dogs really have a theory of mind. For

instance, the experiment with the opaque barrier, when the dog knows what

people can or cannot see, hasn’t been replicated. Moreover, when you are

studying something like a theory of mind, you want multiple experiments where

an animal shows the same set of skills. We have that with great apes, but we

don’t have with dogs yet.

Nogueira: From where

do these remarkable skills of dogs come?

Hare: We tested several hypotheses. The first was that they

were related to wolves, which are clever and maybe are also good at reading

human gestures. The other was experience: they interacted with us and have slowly

learned it. Finally, we considered if it’s something that happened during

domestication. The evidence is mostly in favor of domestication: selection for

friendliness is what allowed dogs to become more skilled at reading and using

humans to solve problems. That was a surprise: why would being selected to be

friendly make you smarter?

Nogueira: How has the Belyaev’ fox

research helped to answer that question?

Hare: This brilliant experiment was conducted by a group of

scientists in Siberia headed by Dmitri Belyaev. They have a control and

experimental line of foxes, separated from each other. The control line was

bred randomly. In the experimental line, Belyaev selected foxes that were

attracted to or enjoyed interacting with people and weren’t fearful. In other

words, Belyaev selected friendly foxes and let them breed together. Over many

generations, the experimental foxes show a high frequency of traits that Belyaev

didn’t select for, such as floppy ears, curly tails, and multi-color coats. The

foxes also had physiological changes related to reduction in aggression and

increased friendliness. This experiment was important to our research because

they have a population that was experimentally domesticated. This was a great

opportunity to test the idea that if domestication really is selection against

aggression and for friendliness for people. It makes sense: how can you have a

domesticated animal if it just wants to attack you or is too scared to come

near you? The foxes also led us to questions about psychology: Is this

remarkable ability of reading human gestures and to use humans as social tools

also a product of selection for friendliness? The answer is yes: the

domesticated foxes acted like dogs regarding their ability to read human

gestures while the control line did not; they behaved like wolves.

Nogueira: You mention in your book that, “without an experiment, we were slipping

from science into the realm of storytelling.” Could you elaborate why we need

experiments?

Hare: We published a paper in Science ruling out the first two hypotheses.1 The first

is that dogs’ remarkable skills of reading human gestures evolved in wolves and

were inherited. Second: lots of experience gives dogs these skills. We didn’t

find any evidence for these hypotheses, so by default we favored the

domestication hypothesis. We didn’t have evidence for it; we only had evidence

against the other two hypotheses. If Belyaev had not done his domestication

experiment, we would have been stuck at that point. Belyaev’s work established

the possibility of testing if domestication made dogs able to read human

gestures. We did an experiment with the foxes and we were surprised: even

though they were not selected to be smarter or to be better at using human

gestures, they were as a result of being selected for friendliness. We had

direct evidence that it was domestication that did it.2 People might

think that we domesticated dogs and made them smarter, but it does not mean

it’s true.

Nogueira: If it’s not true, what probably

have happened?

Hare: People tend to think we created dogs as our own image.

The best evidence suggests that animals had an advantage if they were friendly

to people; they will reproduce more. I was in a restaurant eating outside and

there were sparrows stealing food in a few inches of my feet. Those sparrows

are eating tons of food, they are fat and healthy. That’s because they’re not

afraid of people. I think something like that happened with dogs. In some point

of human evolution, humans created a new food resource that if you could be

friendly enough and not fearful of human population you were a big-time

evolutionary winner. So, a population of wolves chose us; we didn’t choose

them. Since hunter-gathers competed with wolves, it does not make sense to

bring animal like wolves close to your children. The wolves realized, just like

the birds under my table realized, the wonderful resource is scraps around

human camps. After a few generations, they would show morphological changes,

like those we’ve seen in the foxes, so people could tell the difference between

those and the other wolves we competed with. That would be a major selection

advantage.

Nogueira: How

evolution is related to those changes?

Hare: Selection

against aggression and for friendliness toward people creates several changes

beyond that in morphology and psychology. Once these new differences are there,

selection can act on that too. The point is that these new changes were not

created; humans did not think to create dogs with floppy ears, for example.

Some individuals had floppy ears because selection against aggression. Then

people could breed these individuals to make more floppy ears. In other words,

we took the advantage of the variance created by the selection against

aggression. Evolution is not any different to gravity. If I drop a ball, I can’t

stop it from dropping; it’s unstoppable force. Evolution is also unstoppable.

Just because you can’t see, it does not mean it’s not acting all the time. Another example is that there is a white deer that comes to eat in my front

yard. Normally, deer coming near humans is a bad idea. If you live in hundred yards from

my house, a deer in your front yard would soon be dinner. But where I

live in the suburbs everybody think deer are cute and adorable. Where I live,

there is higher proportion of deer with different color coats; there are more

white and albino deer. Research already shows that deer that are invading urban

areas are larger, more social and have more offspring than deer living far away

from humans.*

Nogueira: This

process of domestication that happened with dogs probably have happened with

other animals well, which we called convergence of evolution. What do we find,

for example, when we compare chimpanzees and bonobos behavior regarding

aggression, attitudes towards strangers and so on?

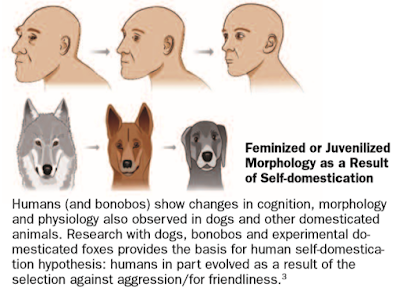

Hare: Bonobos

served as a test-case for the hypothesis that natural selection, and not

artificial selection, caused domestication. We called it self-domestication:

species, through natural selection interfacing with its environment, end up

like a domesticated animal. When we compare chimpanzees and bonobos to wolves

and dogs, many changes between wolves and dogs were found between chimpanzees

and bonobos. Chimpanzees are like the wolf of the ape family. Weather we’re

talking about morphological or behavior characteristics, bonobos are really the

dog of the Ape family.

Nogueira: At Skeptic,

we advocate for evidence-base thinking. Since you had communicated with

the public, what do you think is the best approach to shift people from

faith-based thinking to evidence-based thinking, increasing, for example, the

acceptance of evolution?

Hare: In US,

people think that Christians have a problem with evolution, but the Catholic Church

says evolution is consistent with Catholic doctrine. People love to play the “in

and out” group card: science is something that other people do. If one is

religious and faithful, one can’t believe in science, since science is

anti-religion. That’s the typical in-out group response. People use strategies

to target science, or evolutionary thinking, as the out group. As someone who

studies evolution, the first thing is to notice that humans evolved to see

in-out group everywhere. If you say something like “you’re religious and you’re

not like me”, it’s over. As a science communicator, I’m going to say that

Catholic Church has no problem with my research in order to turn-off the

in-group out-group response. The entire intent of my book The Genius of Dogs

is to get people who had never read about evolution and cognitive science

excited to read about it, because they care about dogs. Darwin intentionally

started The Origins of Species with a chapter about domestication,

because he knew people were familiar with and were not threaten by it. I think

we have to do the same thing.

Nogueira: Thank you for this amazing interview and keep up the fascinating research!

References

1. Hare B, Tomasello M. 2005. Human-like social skills in dogs? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9: 439–444. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16061417.

2. Kaminski J, Bräuer J, Call J, Tomasello M. 2009. Domestic dogs are sensitive to a human’s perspective. Behaviour 146: 979-998 https://doglab.shh.mpg.de/ pdf/Kaminski_et_al_2009a_dogs_sensitive_humans _perspective.pdf.

3. Hare, B Hare, B., Homo sapiens Evolved via Selection for Prosociality. Annu Rev Psychol. 68:155-186: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27732802

4. Hare B., M. Brown, C. Williamson, and M. Tomasello. 2002. “The domestication of social cognition in dogs.” Science. 298: 1634-6.

5. Hare B., et al. 2005. “Social cognitive evolution in captive foxes is a correlated by-product of experimental domestication.” Current Biology. 15: 226-30.

Notes

* Here I corrected a minor mistake that was published in the original version at the magazine. I also corrected Figure 2's subtitle: the correct reference number is 2 (Kaminski et al, 2009).

Notes

* Here I corrected a minor mistake that was published in the original version at the magazine. I also corrected Figure 2's subtitle: the correct reference number is 2 (Kaminski et al, 2009).

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteinteresting, very sophisticated. congratulations.

ReplyDelete